Early RL work on Learning from Human Preferences

- Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences by from OpenAI and DeepMind researchers Christiano et al., published in 2017

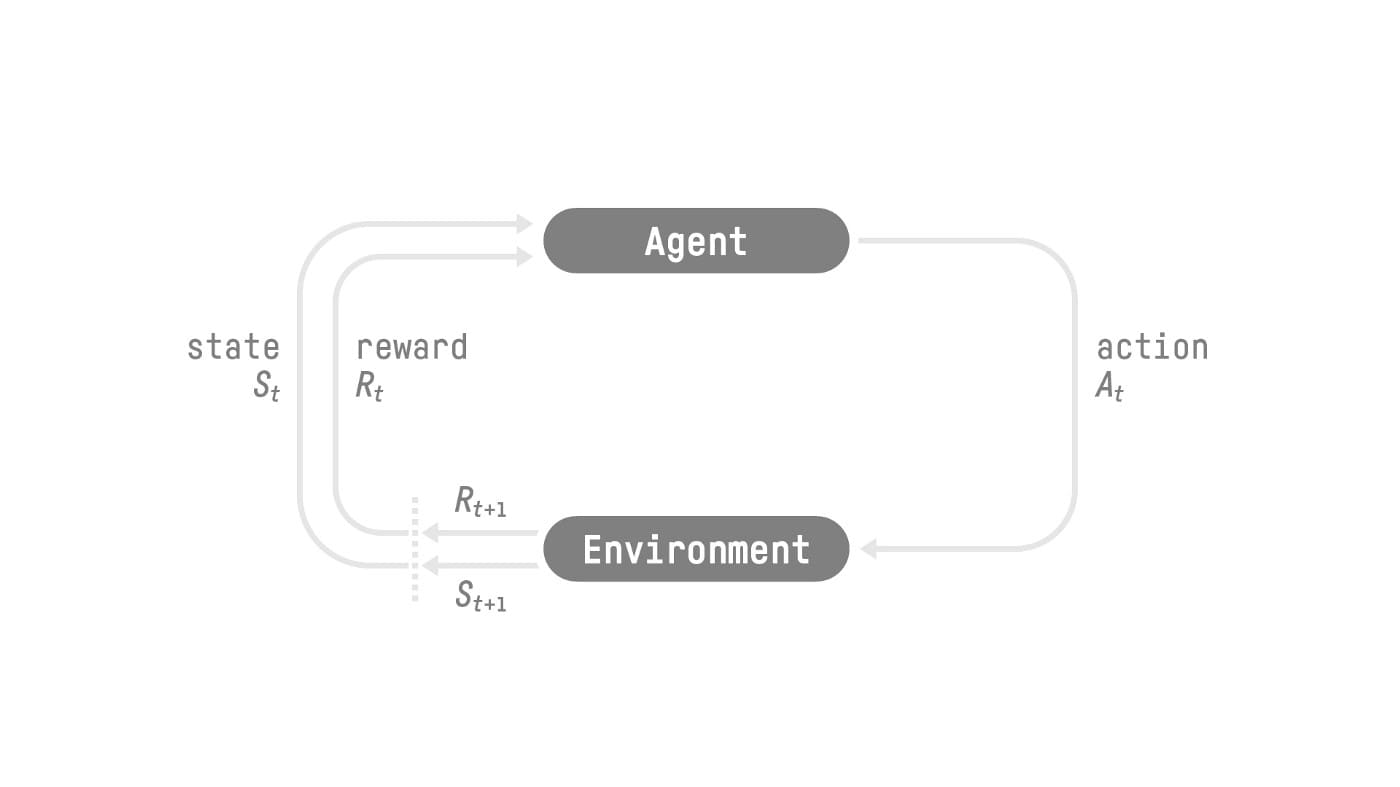

- Basic RL setup: Agent receives State from the Environment. Based on the State, the Agent takes an action, arrives at a new State in the Environment and receive an Reward. Reward is the central idea in RL because it’s the only feedback for the agent, whose goal is to maximize its comulative reward.

- A lot of the early RL work is done on games because they are ideal environments with well-specified reward function to maximize for. It’s difficult to design reward for even simple real world tasks. For example, suppose that we train a robot to clean a table or scramble an egg, it’s not clear how to construct a suitable reward function. One way is to allow a human to provide feedback and use this feedback to define the task, but using human feedback directly as a reward function is prohibitively expensive. Christiano et al. proposed an approach to learn a reward function from human feedback and use it to train an agent that optimizes that reward function

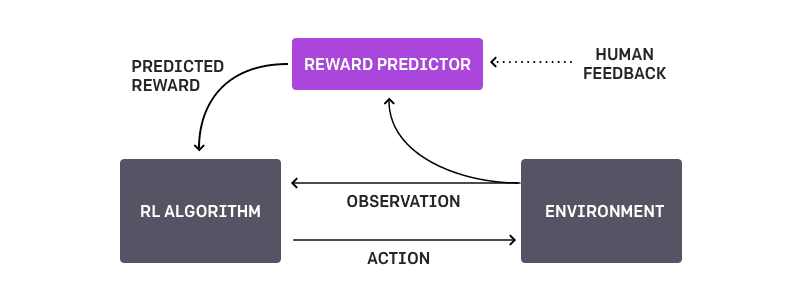

- The method maintains a policy $\pi: O → A$ and a reward function estimate $\hat{r} : O × A → R$, each parametrized by deep neural networks.

These networks are updated by three processes:

- The policy $\pi$ interacts with the environment to produce a set of trajectories $[ \tau^{1}, …, \tau^{i} ]$. The parameters of $\pi$ are updated by a traditional reinforcement learning algorithm, in order to maximize the sum of the predicted rewards $r_t = \hat{r}(o_{t}, a_{t})$.

- We select pairs of segments $\sigma_{1}, \sigma_{2}$ from the trajectories $[ \tau^{1}, …, \tau^{i} ] in step 1, and send them to a human for comparison.

- The parameters of the mapping rˆ are optimized via supervised learning to fit the comparisons collected from the supervised learning to fit the comparisons collected from the human so far

- Results: without the assess the true reward (i.e. the score), the agent can learn from human feedback to achieve strong and somtimes superhuman performance in many of the environments.

- Challenges: The algorithm’s performance is only as good as the human evaluator’s intuition about what behaviors look correct, so if the human doesn’t have a good grasp of the task they may not offer as much helpful feedback.

Apply the above RL technique to Language Models?

- Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences by OpenAI researchers Ziegler et al., published in 2019

- Rather than vanilla supervised learning, the authors finetuned pretrained LM with RL using a reward model trained from human preferences on text continuations. The work is mostly in the domain of RL with NLP being a medium to make RL practical and safe for real-world tasks.

- The motivation is NLP tasks where supervised data sets are unavailable or insufficient, and where programmatic reward functions are poor proxies for our true goals

- Two types of tasks

- continuing text in a way that matches a target style, either positive sentiment or vividly descriptive.

- summarizing text from the CNN/Daily Mail or TL;DR datasets.

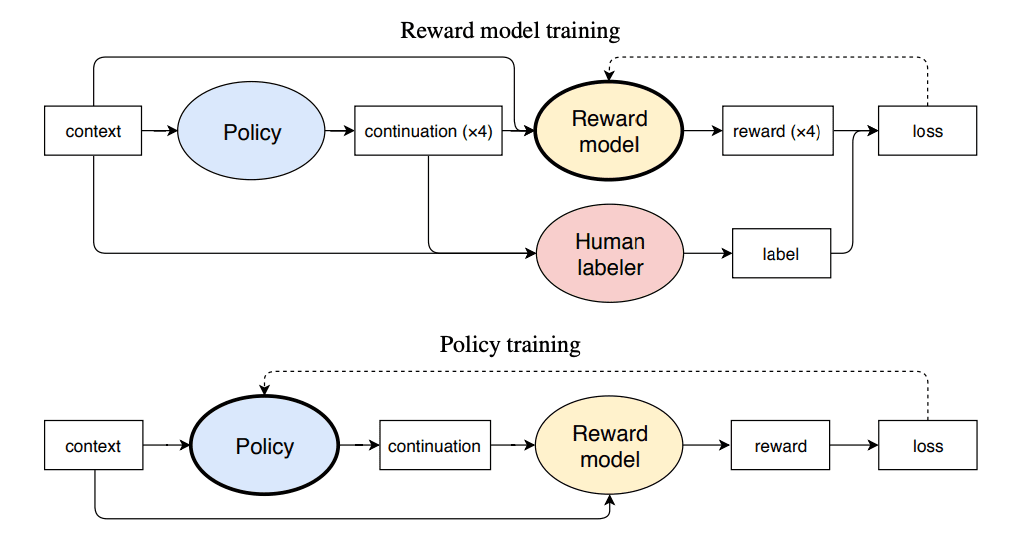

- With the input $x$ (e.g. article to be summarized) and output $y$, we want to finetune the policy $\pi$ (initialized with the pretrained LM, also called the zero-shot policy $\rho$) to optimize the expected reward $E[ r(x, y)]$. However, the reward function $r$ is not provided by the environment like traditional RL and we can only learn about the reward by asking humans. To do this, we use human labels to train a reward model. Following the previous work, we ask human labelers to pick best response $y_b$ to a given input $x$ among four options $(y_0, y_1, y_2, y_3)$. The loss function for the reward model is the classic cross entropy loss after applying softmax over the options.

- The reward model is the language model $\rho$ with a randomly-initalized linear projection on top. To keep $\pi$ from moving too far from $p$, there is a KL penalty, which makes the reward model

- Training process:

- Gather samples $(x, y_0, y_1, y_2, y_3, y_b)$ with y coming from $\rho$ and asking human to pick $y_b$ from the options

- Initialize $r$ to $\rho$ with a randomly-initialized final linear year on top. Train $r$ on the samples from step 1

- Train $\pi$ via PPO, with reward function from step 2

- In the case of online data collection, periodically gather more samples with $\pi$ instead of $\rho$ and retrain the reward model $r$. This is because if the trained policy $\pi$ is very different from the zero-shot policy $\rho$, the reward model will suffer a large distributional shift from training on samples from $\rho$ to evaluation on samples from $\pi$

- Experiments and Results:

- The approach is first tested by using a trained sentiment classification model as a stand-in for human labels. The results showed that RL finetuning is effective at optimizing for the mock sentiment reward

- For stylistic continuation, as little as 5,000 human comparisons is required to result in the RL finetuned model being preferred by humans 86% of the time vs. zeroshot and 77% vs. fine-tuning to the mock sentiment model

- For summaization, the authors found that the while the RL finetuned model underperforms supervised baselines when it comes to ROUGE, they are usually preferred by human labelers. Surprisingly, the RL finetuned models produce summaries that are preferrred over the ground truth! The authors found that the RL finetuned models are essentially extractive “copiers” because copying is easy to check for human labelers.

- Learnings and Challenges:

- Online data collection is hard due to software and ML complexities.

- Since both the reward model and the policy model are initialized with $\rou$, it’s appealing to train jointly to improve learning and efficiency. The authors were not able to make the idea work due to the overfitting caused by imbalanced data (much more RL episodes than reward model data).

- Human preferences and ambiguities can have unintended consequences, for example, since copying is usually correct and easy to check for, the labelers subcontiously preferred copying, which caused the RL finetuned model to be mostly extractive

Analyzing Summarization + RLHF

- Learning to summarize from human feedback by OpenAI Researchers Stiennon et al., published in 2020

-

This is more of an analysis piece as the continutation of the last paper. OpenAI Researchers focuses solely on summarization this time. The initution is that summarization is a field in NLP where training and evaluation are bottlenecked by the data and the metrics (ROUGE) doesn’t align 100% with human judgement of quality. In order to measure human judgement of summarization quality, The authors defined a new metric that tracks fraction of the time humans prefer a model’s summaries over the human-generated reference summaries.

- Key Results:

- Models trained with RLHF is preferred over much larger supervised models by human evaluators. This is evaluated through the percentage of summaries generated by that policy that humans prefer over the reference summaries in the dataset. The fact that most of the RLHF numbers are greater than 50% here is astounding

- 1.3B RLHF model outperforms a supervised model 10x the size

- 6.7B RLHF model outperforms the 1.3B RLHF model, which shows that RLHF benefit from scale

- Policies tuned on reddit datasets transfer to news articles dataset without any in-domain finetuning.

- Although underperform the reference summaries, the RLHF model transfers much better to the news articles domain compared with supervised model finetuned on reddit dataset

- 6.7B RLHF model performs almost as well as a 6.7B model finetuned on the news article dataset

- Analysis on the reward model

- optimizing against the reward model (by decreasing the $\beta$ term on the KL divergence penalty) yields some improvement when at first but eventually overfits as the policy collapsed into a single mode

- the reward model performance scales with increasing model and data size

- Models trained with RLHF is preferred over much larger supervised models by human evaluators. This is evaluated through the percentage of summaries generated by that policy that humans prefer over the reference summaries in the dataset. The fact that most of the RLHF numbers are greater than 50% here is astounding

Putting it together: InstructGPT

- Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback by OpenAI researchers Ouyang et al., published in 2022

Methodology

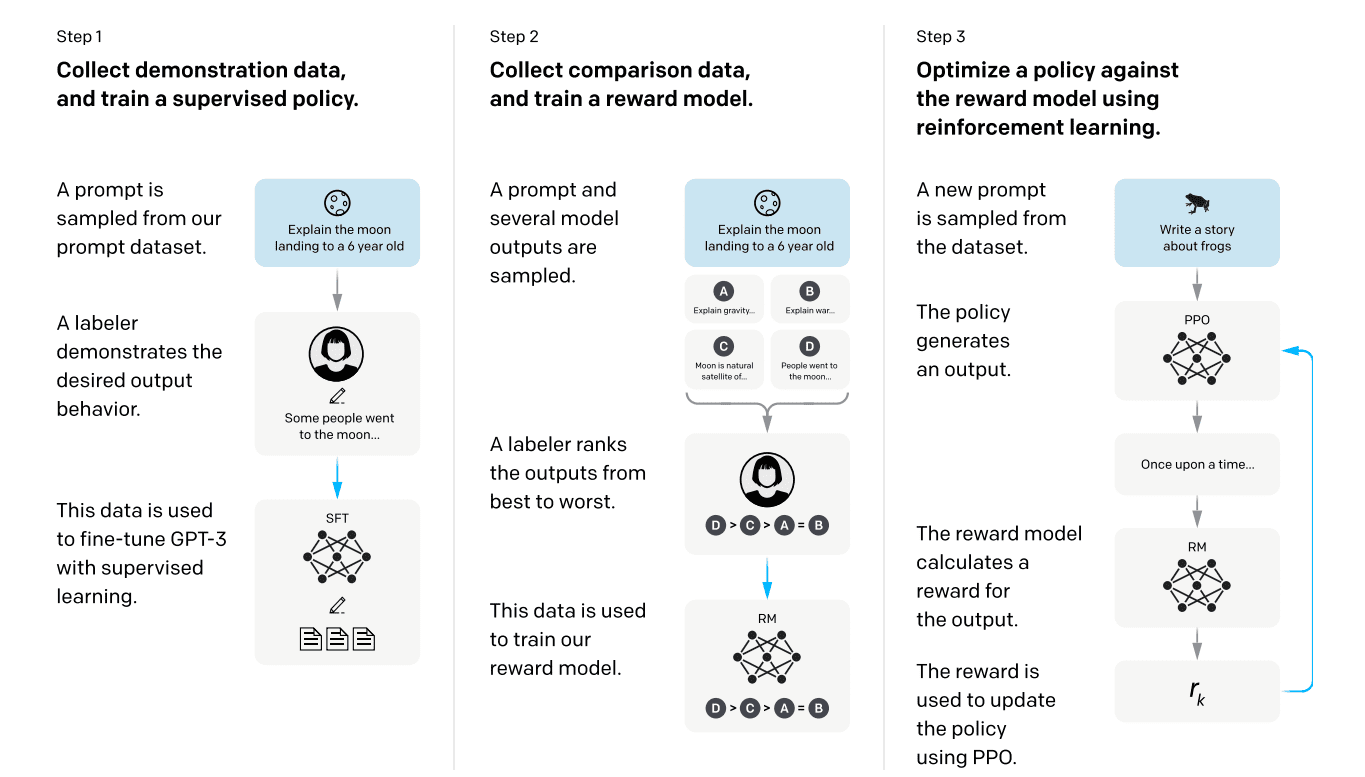

- Similar RLHF techniques as previously introduced, with some modifications for the unique goal of this model

- Collect demonstration data, and train a supervised policy: collect human-written demostrations on a wide variety of tasks, which is then used to finetune the model with supervised learning previously the supervised learning is done on existing dataset (text continuations, summarizations) which doesn’t require labeling new data. The authors wants to train on text prompts submitted to the OpenAI API and also hand-written by the labelers themselves, which clearly has no labeled data, hence the labeling effort.

- Collect comparison data, and train a reward model: collect a dataset of comparisons between model outputs, where labelers rank output from most-preferred to least-preferred for a given input. The comparison dataset is then used to train a reward model to predict the human-preferred output. The authors only used a 6B reward model to save compute. this is different from previous RLHF setup where labelers labeled pairs for the reward model with binary cross-entropy loss. The labelers here ranks the outputs for efficiency purposes, as one ranking data point can turn into ${ K \choose 2} $ pairs. The reward model still uses binary cross entropy loss. The authors put all ${ K \choose 2} $ pairs into the same batch to improve efficiency and prevent overfitting

- Optimize a policy against the reward model using PPO: Use the output of the RM as a scalar reward to finetune the supervised policy to optimize this reward using the PPO algorithm. identical to previous setup

Results

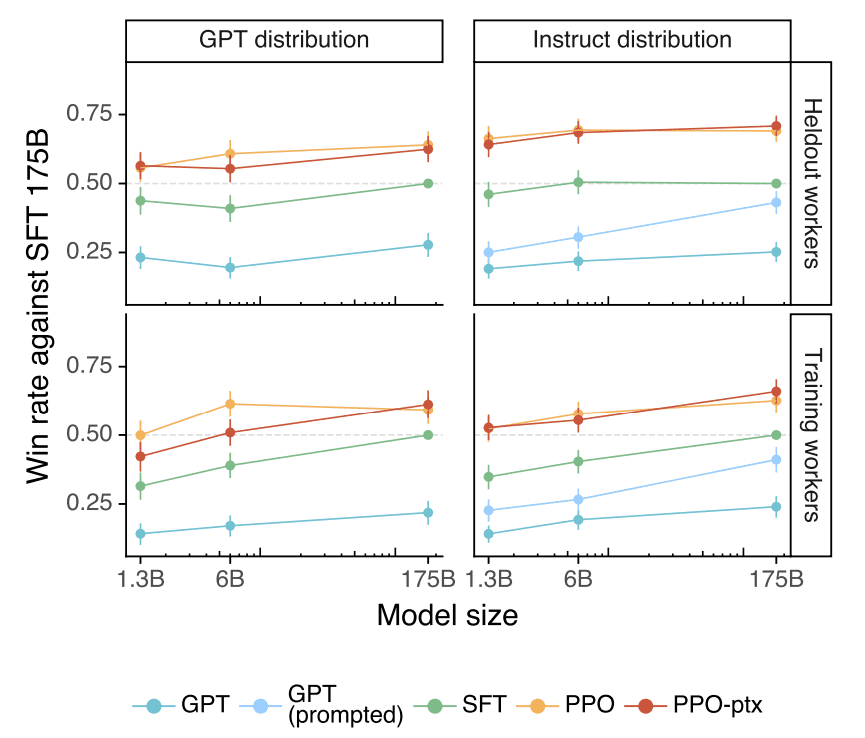

- Using the same labeler preference metric as Stiennon et al., we can see that labelers significantly prefer InstructGPT outputs over outputs from GPT-3. 175B InstructGPT outputs are preferred to GPT-3 outputs 85 ± 3% of the time, and preferred 71 ± 4% of the time to few-shot GPT-3. Other than an expected gain with model scale and PPO models outperforming GPT and fewshot GPT, we can see that even 1.3B PPO model can outperform the vanilla 175B GPT!

- The authors also observe the same improvement on the held-out labelers ( since labelers provided the demonstration data that trains the SFT model and the ranking data that trains the reward model, we need to rule out that PPO model simply captured the personal preference of the labelers.).

- Demonstration data is more refelctive of real world LLM usage than instruction tuning dataset converted from classic NLP datasets: if we try to finetune 175B GPT-3 not on the SFT data, but on the instruction tuning datasets FLAN and T0, we find that these models perform better than GPT-3, on par with GPT-3 with a well-chosen prompt, and worse than our SFT baseline. This is because the classical supervised NLP datasets that FLAN and T0 are based off are a small percentage of the API distribution and the input distribution lacks diversity.

- InstructGPT models show improvements in truthfulness and informativeness over GPT-3, without being specifically instructed to tell the truth. Not really surprised here. Even without specifically instructed to tell the truth, the labelers would downrank the uninformative and untruthful generation outputs, which is then learned by the reward model and eventually the PPO model

- when instructed to produce a safe and respectful output (“respectful prompt”), InstructGPT models generate less toxic outputs than those from GPT-3

- When training the PPO model on the API distribution, the performance on public NLP datasets decreases because of “alignment tax”. This can be minimized by adding a pretraining updates to our PPO fine-tuning. Adding the pretraining updates performs better than the simpler solution of increasing the KL coefficient